What is RSV (Respiratory Syncytial Virus)?

RSV causes infections in the lungs and respiratory tract, and mostly affects young children (1–3). For adults and older, healthy children, the symptoms of RSV are similar to the common cold. This may include runny nose, dry cough, low-grade fever, sore throat, sneezing and headaches (3). For infants, older adults, and immunocompromised individuals, symptoms can include more severe infection and difficulty breathing and/or wheezing (1,3). RSV is a major cause of infant hospitalization and can lead to serious complications such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia (3–6).

RSV is highly contagious, with transmission occurring during respiratory secretions from an infected individual (e.g. droplets from coughs, bodily surface) or from touching a surface contaminated with the virus (4).

How infants are protected: There is currently no routine RSV vaccine given directly to young infants. Instead, infants can be protected by maternal vaccination during pregnancy or by receiving long-acting monoclonal antibodies after birth (see below) (4,5).

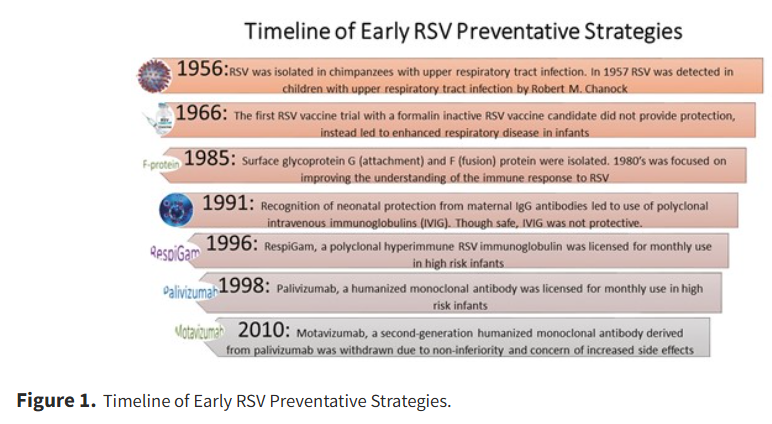

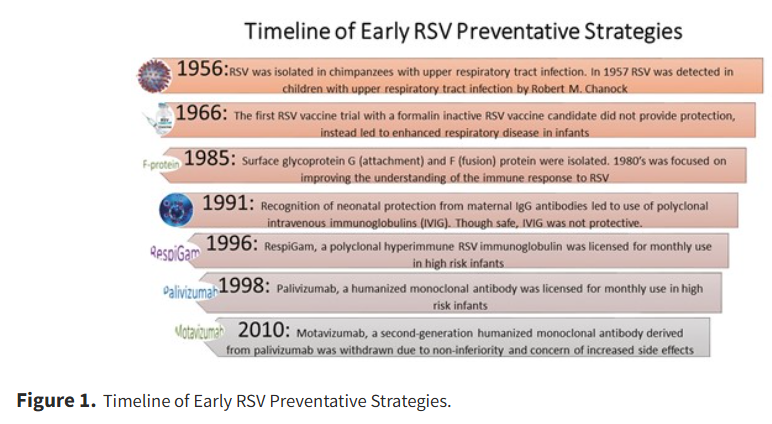

A History of RSV and the RSV Vaccine

The first identified case of RSV was by American pediatrician and virologist Dr. Robert M. Chanock in 1957. The virus was thought to have originated from chimpanzees (7) but was later discovered to be primarily a human virus. Vaccine development then began in the 1960s, with limited success (7). In the 1990s, vaccine development using humanized monoclonal antibodies was found to be both safe and effective. (Picture: Noor et al., 2024)

Advances in medical sciences have led to continuing efforts in developing RSV vaccines to tackle the global health challenge (8). As of 2020, there are several vaccine candidates in the pipeline directed toward different target populations: infants younger than 6 months, children older than 6 months to 2- to 5-year-old children, and the elderly (8). Recent research has made promising progress in RSV mRNA vaccine development (9). Safe and effective RSV vaccines will significantly decrease the burden of acute RSV disease and the long-term respiratory morbidity associated with this disease, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Is it Safe?

Receiving the RSV vaccine during pregnancy is safe and there is no evidence that the RSV vaccine will harm your baby (6). Large trials and post-authorization monitoring support the safety and effectiveness of Abrysvo given at 32–36 weeks of pregnancy to protect infants. The Canadian Immunization Guide currently recommends different immunizations to protect infants (4); one is administered to the pregnant individual during pregnancy, and the other is administered directly to the infant.

Why the RSV Vaccine Matters for Pregnant Individuals and Infants.

The RSVpreF vaccine (AbrysvoTM) is administered to the pregnant mother to protect the infant and is recommended to be administered to pregnant women during weeks 32-36 of their pregnancy (4,10).

Nirsevimab and Palivizumab are two monoclonal antibodies that are administered directly to the infant, if the mother did not receive the RSV vaccine during pregnancy or if the infant is at increased risk of RSV infection (4,10).

How does the RSV Vaccine Work and How is Immunity Passed to your Baby?

RSV vaccines given to the pregnant individual allow for antibodies to be transferred from the mother to the baby in the womb (6,7). Antibodies are protective proteins that are produced by the body that protect against infection (6). As a result, these antibodies give your baby protection against the severe effects of RSV for up to 6 months after they have been born (6).

Global Trends: Receiving the RSV Vaccine during Pregnancy Reduces RSV-related Hospitalization in Infants:

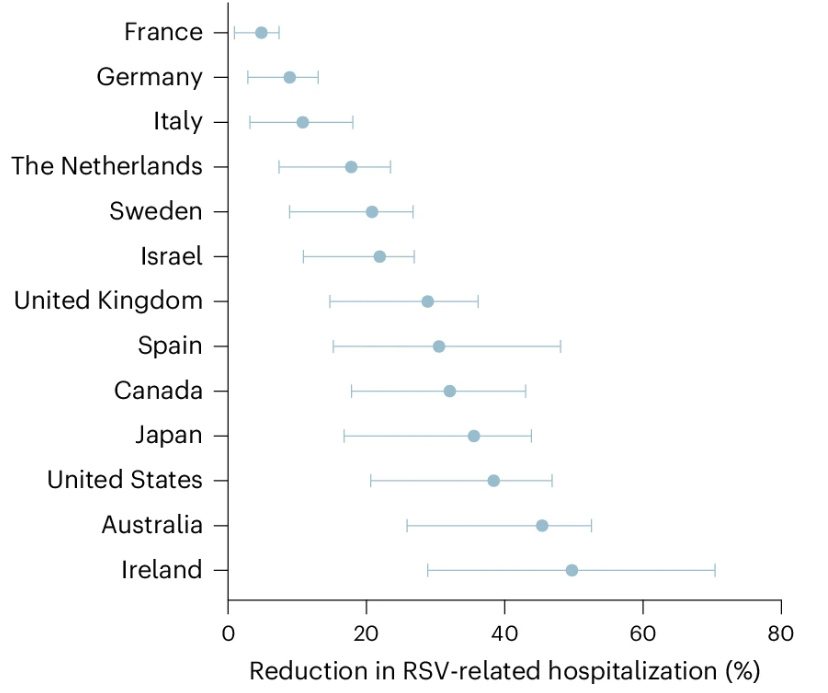

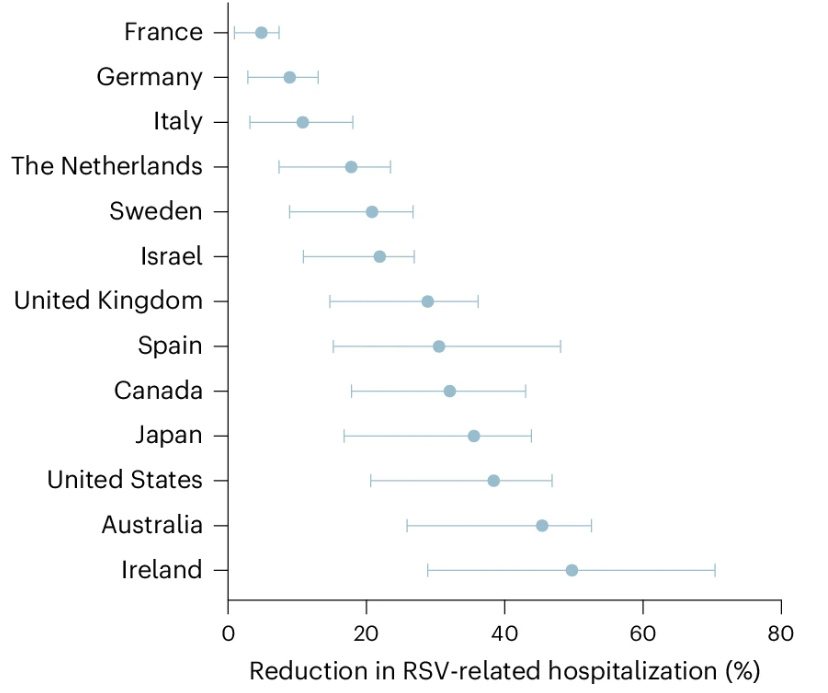

Research into RSV vaccinations has been ongoing and scientists continuously discover more about the disease and its prevention (11). One study found that vaccination of pregnant women could reduce infant hospitalizations by 5–50%, with findings from 13 different countries (11).

Picture: Estimated reduction in RSV-related hospitalizations in infants. (Du et al., 2025)

Barriers and Facilitators of RSV Vaccine Uptake:

Primary barriers regarding RSV vaccine uptake during pregnancy are mostly represented by concern regarding the safety of vaccines for both the mother and the fetus and concerns about vaccine efficacy (12). Other barriers include negative personal/family experiences regarding vaccinations and limited access/cost of prenatal care (12).

Facilitators of RSV vaccine uptake during pregnancy include clear communication, trust-building and community engagement between individuals and healthcare/education providing institutions (12). Notably, strong recommendations from a healthcare provider, perceived benefit of the vaccine and access to healthcare were also factors that facilitated vaccine uptake during pregnancy (13).

Conclusion:

Pregnancy is a critical period for protecting health, and the RSV vaccine offers a powerful tool to support the well-being of both mothers and their babies. Getting vaccinated against RSV helps prevent severe illness during pregnancy and provides early immunity to newborns with strong evidence supporting its safety and effectiveness. RSV vaccination for pregnant individuals remains an important public health goal to ensure healthier outcomes for mothers and infants in Canada.

References:

By Angela Xu